Uplift

Uplift

conservation on the colorado plateau

Uplift

Uplift

conservation on the colorado plateau

As we face the future of life on the Colorado Plateau, it can be hard to fathom what our world will look and feel like given the complexities and uncertainties of climate change. Ecologists, hydrologists, and climatologists are developing predictions of what this place will be like as our climate shifts, but challenges arise when this complex information needs to be relayed to our community.

Created by:

Kate Aitchison

Artist

Collin Haffey

Fire Ecologist

Cari Kimball

Environmental Sociologist

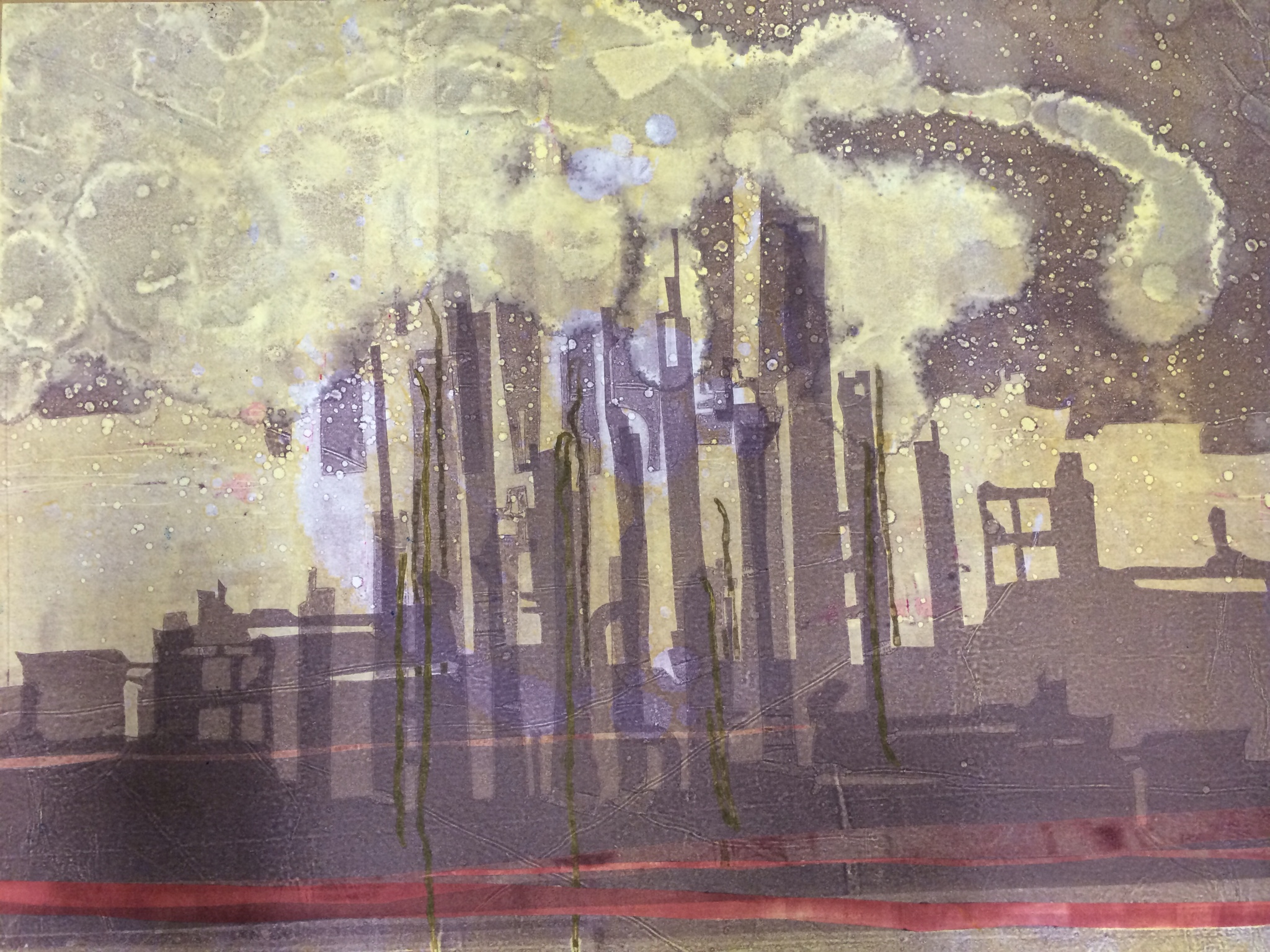

Burnished Landscape

Burnished Landscape

Show @ Firecreek

Flagstaff, AZ

Burnished Landscape

Burnished Landscape

Show @ Firecreek

Flagstaff, AZ

In the spring of 2013, we embarked on an exploration of how science and art can work in tandem to provide people with a more powerful statement of how climate change is impacting Southwestern forests and the shifting trends of forest fire toward the big and bad end of the spectrum.

We paired Flagstaff artist Kate Aitchison and environmental science and policy graduate student Collin Haffey with the goal of answering the question: “what will the future of the Colorado Plateau look, feel, smell, or sound like? And how will we mitigate and adapt to these changes?” The two worked together over several months to explore the predicted impacts of climate change on Southwestern forest fire regimes. In December of 2013 we developed The Burnished Landscape, a collaborative exhibit that displayed the Aitchison’s art next to scientific information about changing climate and fire regimes. During the exhibit we engaged visitors in conversations about the project, the science behind it, and ultimately the art the project inspired. The exhibition opening was well attended and the work on display spoke strongly to people. Through this project we found an innovative way to communicate a sense of urgency with guarded hope given the best available forecasts for the future of the distinctive and inspiring landscapes of the Colorado Plateau.

We used our experience with Burnished Landscape to develop a project in southern Utah, where we served as Artists in Residence for the Entrada Institute in Torrey.

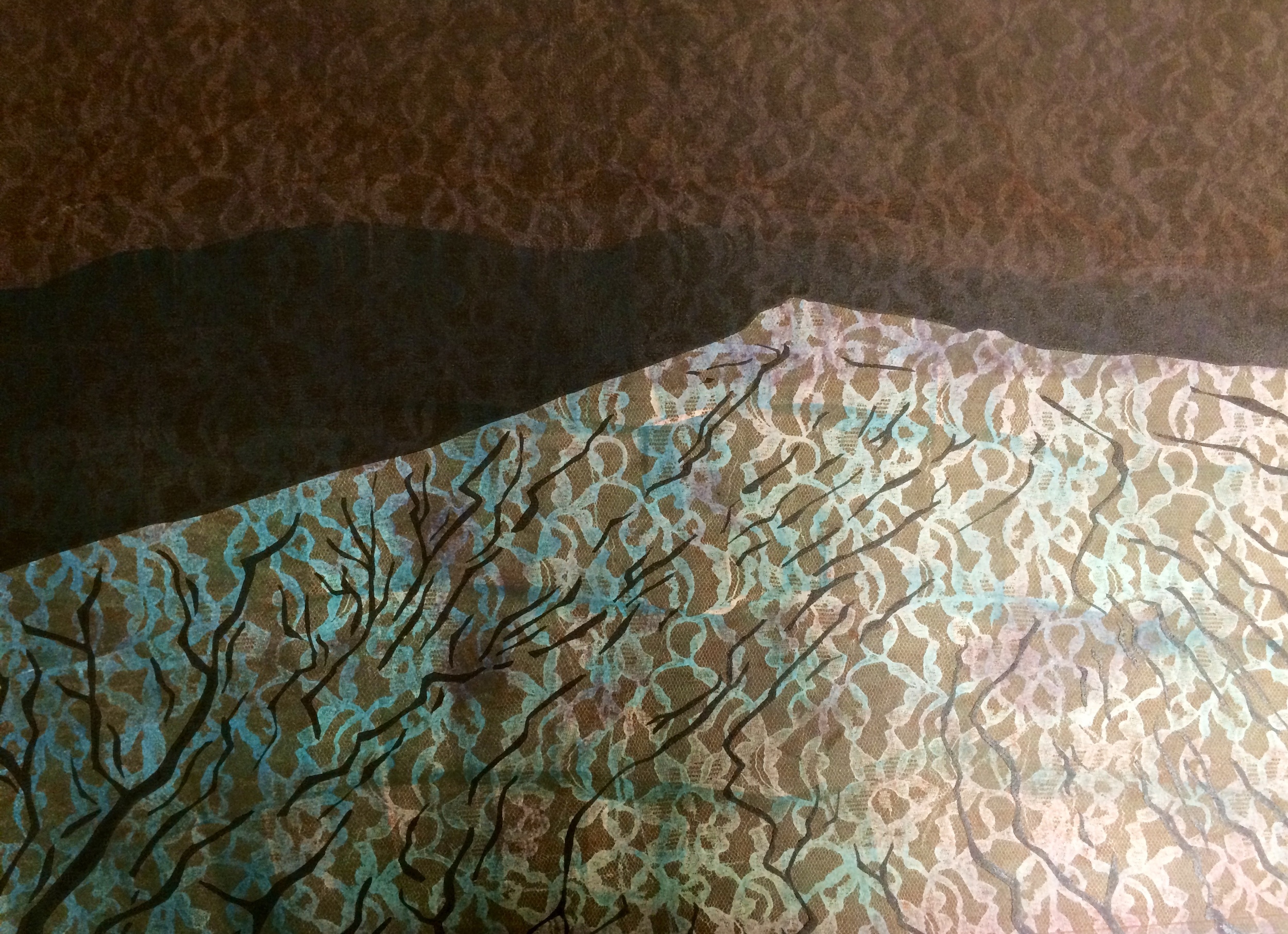

Southern Utah

Southern Utah

a road trip for conservation exploration

Southern Utah

Southern Utah

a road trip for conservation exploration

To prepare for our artist in residence project for the Entrada Institute in southern Utah, we got together at a small cabin in Bluff. There, we asked ourselves “why are we here?,” “what draws us to this place?” While these questions seem a little bit existential, we felt answering them was key to creating the best possible mutualism between art and science. As we traveled through the canyons and across the mesas to Torrey, and in and out of the Book Cliffs, these questions lingered in our minds. In an area where landscapes are forever old and infinitely vast, it is hard not to feel insignificant. In a society where those with the most often speak the loudest and drown out the many with the least, it is hard not to feel powerless.

Together we struggled with the thought of being insignificant and powerless. It seemed that through this struggle we found the answer to our questions: we were here because we are afraid of losing parts of the landscape that mean the most to us, afraid of having the landscape be altered to the extent that all our connections to it are severed. It is these connections, intellectual and emotional, that draw us to this place. The connections that strengthen each time we visit our favorite canyon, mesa, or mountain, every time we see something new and remarkable.

All across the Colorado Plateau, the human connection to the environment is evident. With a little research and observation you discover that the people who came before us depended on the connections between each other just as much as their connections to the landscape. The ancestral used their connections to each other and to place to survive in this harsh environment, conserving the land and living off it at the same time. Since then, conservation has evolved, the process has changed but the fundamental drivers remain the same. We created this show to highlight today's conservation process, as we see it.

“As conservationists we are often introduced to issues through a lens of despair. ”

Despair

Despair

a rough beginning for good things

Despair

Despair

a rough beginning for good things

Examples of despair are not hard to find, in southern Utah the potential for oil sands development in the Uinta Basin is a case study for environmental despair. Our thirst for oil compels us to search for ever more invasive means of extracting fossil fuels as our supplies dwindle. The development of oil sands in Alberta, Canada has left and continues to expand vast scars on the landscape, bringing economic and technological advancement, but at what cost? Based on the lessons learned from the Canadian oil sands development, we know that the immediate local environmental impacts to areas like the Book Cliffs can be devastating, especially given that bitumen extraction in the Uintah Basin would essentially be done through strip mining. Communities in the Uintah Basin can anticipate air quality impacts, groundwater depletion or contamination with industrial solvents, and effects on human and wildlife health. For example, Canadian communities close to oil sand development sites have seen spikes in rates of cancer. On a global scale, oil sands development serves as a cheat code for climate change, allowing carbon emissions to jump to highest emission scenarios essentially overnight (geologically speaking).

Fire season across the west is getting longer and hotter. Recently we asked a fire manager at the Grand Canyon how long he defined the fire season for planning purposes; he responded flatly, "It's pretty much year round." A member of a southwest incident management team, those that respond to the most complex fires, told us they had plume dominated fire for 36 straight hours, something he has never seen in 30 years of fire fighting experience. In the Southwest a "big" fire in the 1970s was anything over 10,000 acres, now fires almost annually burn 10 to 50 times that large. The size of high severity or treeless patches in ponderosa pine forests is unprecedented in the evolutionary history of the ecosystem and is now causing a conversion from forest to non-forested shrubland or grassland.

“As conservationists, in the face of despair we are compelled to seek connections that may lead to solutions. ”

Despite aggressive advocacy and outreach to the hunting community, lead poisoning – mainly from bullet fragments – continues to be the number one killer of California Condors. In California the ban on lead ammunition has also failed to help bring population numbers to sustainable levels and the condor continues to be a conservation dependent species.

Habitat loss continues to drive the extinction of many species around the west. Whether it is urban sprawl, road construction, or oil and gas development habitats continue to be converted, and fragmented, due to human use. In a recent paper, it was estimated that 3.7 mil ha of sage brush shrubland, and 1.1 million ha of grassland would be negatively impacted by oil and gas drilling in the intermountain west (Copeland et al. 2009, PLOSone), an area equivalent to half the size of the state of Indiana.

All of these forlorn conservation problems are placed on top of a plateau that is going to get hotter in the coming decades. The recent IPCC report revised the "best case scenario" for global temperatures to be at least 1 ̊C warmer by the end of the century, the "worst case scenario" – our current trajectory – projects a 4 ̊ C warming. A 4 degree C temperature shift would drastically reorganize ecosystems on the colorado plateau. A recent study published in the journal Nature Climate Change calculated the atmospheric moisture demand, essentially how "hard" the air is pulling water from tree leaves. The study used tree rings and calculated the atmospheric moisture demand going back to 1400s. With projected climate change the atmospheric moisture demand at mid-century (i.e. 2050) could be 2 standard deviations greater than it was during the mega drought of the 1500s. An event that forced the rearrangement of people across the CO plateau. This means that the current drought will feel like a relatively wet period.

Connections

Connections

Connections

Connections

As we step back and look at all these various issues as a whole, they seem overwhelming. Climate change creates positive feedback loops in which loss of habitat, decrease of air quality, and change of fire regimes are quickened or intensified. Disparities of wealth drive policy creation that favors the status quo, doing little to address climate change drivers. These issues are multifaceted and have been growing and morphing for decades. In order to address them, we’ll need to take actions that are equally multifaceted and consider the long term interests of our communities. What gives us hope is that the need for multidisciplinary work means that people from all walks of life can contribute to the improvement of our future prospects. At the end of the day, human activity created the problems we face and we can rely on human ingenuity to correct course, but we must intentionally choose to do so.

As residents of the Colorado Plateau (or anywhere out West) we all have a sense of the power that place can hold. People from all over the world visit the American Southwest to see these dramatic, breath-taking landscapes. Many of these spaces have already been given state-protected status, but the issues we face are not confined to administrative boundaries. Additionally, each of us have places – a favorite stand of piñon or a trail where you walk everyday, observing gradual transitions between seasons and across years like the added wrinkles on the face of an old friend – these places on their face might seem ordinary, but they become extraordinary as your connection with them grows over time.

“In the west it is often the place that attracts us and the people that keep us. No matter how old or young your connection to place, the connection to people feels much older. Perhaps because we all share a legacy of ethics, of traditions, and of struggles. Losing oneself in the vastness of western landscapes compels us to reach out to like-minded individuals. We seek to amplify our collective effect during our short stay in a landscape defined by deep time. ”

Diversity of Action

Diversity of Action

Diversity of Action

Diversity of Action

Environmental issues are complex and often lack a clear solution, therefore diversity of action on conservation issues can often lead to creative solutions that protect the places we love.

As conservationists we feel diversity of action is essential because:

- The issues we face are diverse.

- It’s a more holistic approach.

- It challenges norms and conventional wisdom.

- It’s fun.

- It leads to stronger, more durable solutions.

- It allows for greater appreciation of self and others.

- It strengthens communities and relationships.

- It allows for multiple pathways to understanding.

- It creates more just outcomes

“As an environmental sociologist, I feel that diversity of action is essential because involving community members in an environmental issue creates ownership in that issue, allowing for stronger solutions.”

We've talked to a lot of people about how to "do" conservation. Their answers have been all over the map. Take for instance the guy who designs environmental protection and mitigation projects for a copper mining company. He sees that as a pragmatic way to make a real difference. Our society has a huge demand for copper, mining copper is an inherently negative impact on the environment, but there are ways to mitigate some of the damages and do the actual mining in a way that is the least environmentally devastating.

We have spoken with senators from western states who spend a few weeks a year at the State House working toward conservation legislation that does not eliminate the human presence on the landscape but attempts to honor the needs of the land and the needs of the people, understanding that there is no separation.

We have met with activists and pragmatists and realize that people are as complex as the landscapes they care for. We like meeting with people, because people can have internally competing views and often have lots of self doubt about the effectiveness of their actions.

In that vein we spoke with Tom Sisk, the director of Landscape Conservation Initiative at Northern Arizona University, who has recently worked to facilitate and provide data for several multi-stakeholder collaborative decision making groups. The goal of these groups is to highlight areas of agreement – on a map – where the entire diverse group can agree on the needed action. In Tom's experience much of the disagreement occurs over a very small part of the landscape and people can generally move toward action on the areas they agree on while continuing to discuss the desired outcome on a small portion of the landscape.

This hard, often long, and sometimes tedious process has lead to some of the most rewarding work of Tom's career. He talked about how sometimes the scientific process can seem too linear to capture all of the complexity of an issue. And that working with a diverse group of people tied closely to a specific landscape can reach conclusions that are often validated by natural experiments. That is not to say that the pure science Tom does is not valid or useful, quite the contrary. Tom, and the other members of his research lab, are always analyzing the effectiveness of the collaborative process, as well as tracking ecological trends with the hopes of incorporating their findings into conservation action.

“ We believe in the future of this place, and the people that live in it, and we want to find solutions to make our world more sustainable for the future. This place is our future, and we are going to fight for it.”

Moving Forward

Moving into the light

What comes next?

Moving Forward

Moving into the light

What comes next?

From the experiences of successful conservationists like Tom we learn that making connections, between people or disciplines or issues, serves to both advance conservation work more effectively and to make the work more enjoyable in the process. Beyond that, actually, we aren't entirely sure what comes next, but we do know that these science-art projects are super fun. For more of our musings on these collaborations, check out our art blog posts on L-C-Ideas.

Artwork and Photography by Kate Aitchison

kateaitchisonart.com